Updated: December, 2023

© 2023 Think Social Publishing, Inc.

Hi, I'm Michelle Garcia Winner. I am the founder of Social Thinking and I continue to work with clients as they are my fuel! When I'm having a bad day and get to work with clients, I always feel better, I just love the engagement and how much I learn. It surprises my clients when I tell them that I learn from them—because they think they're coming to learn from me. It's really nice when it goes both ways.

Let me share with you a few “Ahas!” I recently had working with a fourteen-year-old girl who is a freshman in high school. I had been working with her brother for the last four years and would meet this girl on-and-off as the family came together to the clinic. On occasion, the parents would take me to the side and let me know that their daughter was struggling with social anxiety. Finally, a few months ago they asked if I would work with their daughter to see if I could provide any help.

I'm a speech-language pathologist, but I've learned a lot about social anxiety because so many people with social learning challenges and self-awareness—regardless of their diagnosis—tend to struggle with social anxiety. I've learned a lot of strategies.

I learned that my client doesn’t currently have a diagnosis. She is known to be an excellent student. She attends a hard-push high school and has lot of talents, yet her teachers are giving feedback to the family that she doesn't talk in class. They say if she can express herself more, it will help her grow.

As I started to work with her, I saw her as a kid with a lot of traditional social anxiety. She does have four friends with whom she feels included, and in fact, she doesn't feel highly anxious when she's with her friends. It's just the rest of the time. First, we defined where the anxiety shows up. The anxiety tends to show up with teachers or with any kid who is not part of her inner friendship circle. The social anxiety sometimes shows up, for example, when she is with her parents, and they want to take a picture of her in her dance costume. Interestingly, she doesn't have anxiety while dancing, but she does have some social anxiety once people pay attention to her after she dances.

Here was my first Aha!—there are traditional strategies for social anxiety that have been helpful. We've been figuring out her inner coach and her self-defeating comments. We’ve been figuring out how to create a more positive mindset and then we've worked on how she can step-by-step communicate a little bit more in class. We started with priming, then moved on to her raising her hand once a week during a class where she felt comfortable. If she could imagine her success, then she could raise her hand. She did that in one class and found it to be much easier than she feared it would be.

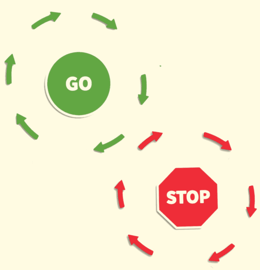

Through this journey, we also determined that her peers, teachers, and the kids she doesn't know are all really supportive of her. Even if she flubs up, she really doesn't think people are going to make fun of her or talk about her. So, in her mind, she has this idea that the social judges are all pretty positive. But her “self-defeating” voice is still pretty mean and makes her think (in that moment) how awful it would be if she messed up. In fact, she feels like she can’t take the risk. Her “inner coach” voice, on the other hand, is a more rational but weaker voice that tells her “You know, people really are pretty nice to you. You go to a nice school where people have never made fun of you even though you've always been quiet.”

What’s the power of these two voices? We used our hands like puppets to impersonate them. First, she worked on her “inner coach” voice by moving the “mouth” of her hand puppet while speaking in the voice of that character. That's a nice Aha!—getting kids to a place of using more than just language can be powerful. Moving her hand and body toward these different voices made her more focused. She then named her voices—by personalizing them it helped her focus on what's going on in her head in class when her actual voice shuts down.

The next week she had a goal of raising her hand two times, one time in two different classes. But here was the problem: it turned out in the second class where she was going to raise her hand the opportunity never came. So, she was getting anxious in the class just waiting, but there wasn't a natural point for her to raise her hand, make a comment, or answer a question. However, it turned out that other kids were raising their hands, she just didn't feel like there was a natural opportunity. I told her, “You know, you don't have to wait to comment or answer a question. You could always just ask a question,” and then I watched her shudder and look as though she was shutting down. I asked, “Do you have a problem with asking questions?” and she responded, “I've never known how to ask questions. I just don't know how to do it. I don't know how people figure out the language for asking a question.” And there was another Aha!—if she went to a mental health counselor, she would be diagnosed with social anxiety. The evidence was pretty compelling, very persistent, and a long-term issue. One question we look at, especially as social communication specialists, is what is happening below the level of social anxiety at the level of communication that may make anxiety more profound. For example, what if you don't know how to answer or ask a question or sustain an interaction? These issues would contribute to compelling anxiety.

So, I talked to her family about a couple things. I let them know she needs to work on the language aspect of social communication in terms of how and why we ask questions. She needs to practice forming questions. She needs to practice initiating communication. She's not a great initiator—even with her bonded friends. They do all the setup and then bring her into, for example, a weekend event. Only at that point will she bring her voice into the group, but she never initiates getting together with friends on her own.

These issues present social communication challenges, not just anxiety. We know from the research that 68% of siblings of people diagnosed as autistic have a compelling learning disability. Her brother had a late diagnosis of autism, and his sister is presenting with social anxiety and underlying social communication challenges.

Here is my fourth Aha! I said to her, “You know, if the teachers aren't providing a clear opportunity for you to raise your hand, then that makes it very hard for you to practice communicating with folks. What do you think about telling the teachers that we have a plan? You can tell them that you are working on this in class and that it would be great if they could help you by calling on you once a week.”

We wrote a script and she practiced with me from across the table. That part was counterintuitive to her—why would you talk to someone about your problem of not talking? But then we discussed that teachers are people who are there to help. They've already told her parents their concerns, so maybe if they knew she is working on speaking up in class they would make it easier for her to practice. That sounds easy, but with social anxiety, it is not easy at all.

She needed to feel comfortable enough practicing what she wanted to tell her teachers inside of the therapy room before doing it at school. So that meant reading the statement that she wrote. I helped her form the statement in her own words (I think that's important) while at the table. But then I had her stand up and practice. Next, I had her move further away and approach me to get my attention before she read it. At that point she said, “Why do I have to do this? I already know the words. Why do I have to practice this?” I replied, “So that you practice what to do with your body because communication is not just words—it’s a whole body experience.”

She started on the other side of the room, then would walk up to me and say what she had to say. Then she would start outside the door, go through the door, walk up to me, and make her statement. After that she would start off down the hall, walk through the door, and come up to me to say the same thing. She noted that at first it felt pretty awkward, but the more she did it the more she internalized the pattern. With social anxiety, this method is well-known as part of treatment. My Aha! around this (and something I've been working on for years with all my students) is when practicing it is not good enough to just walk across the room. Instead, it’s best to actually begin outside or down the hall and walk through the door to really embody the movement of initiation—the physicality of communication as well as the language.

The following week she went to school and was comfortable talking to one teacher. She later told me that because she had practiced so much she felt like she could do it. The teacher said, “That's great—I’ll absolutely help.” And the very next day the teacher called on her in class. We’re on the road to her getting more practice with the help of environmental supports! It was because she let them know how to help her.

Related to all of this is a free article on our website called Anxiety and Social Competencies (The Spirals). I have also used the Four Steps of Communication with her quite a bit. We are now working on developing her executive functioning by using goals/action plans, inner voice, self-defeating voice, and other strategies.

Good luck! I know we're all dealing with a lot of anxiety no matter what your profession. We all need to just keep learning and have our own Aha! moments. Thanks for taking the time to learn with me